🗓️ Date Published : 03/12/2022

<aside> ➡️ In first this part of the conversation, Parmesh talks about how he understands his work as a “corporate activist”, about his theory of change and about the parental burden of the Indian workplace.

</aside>

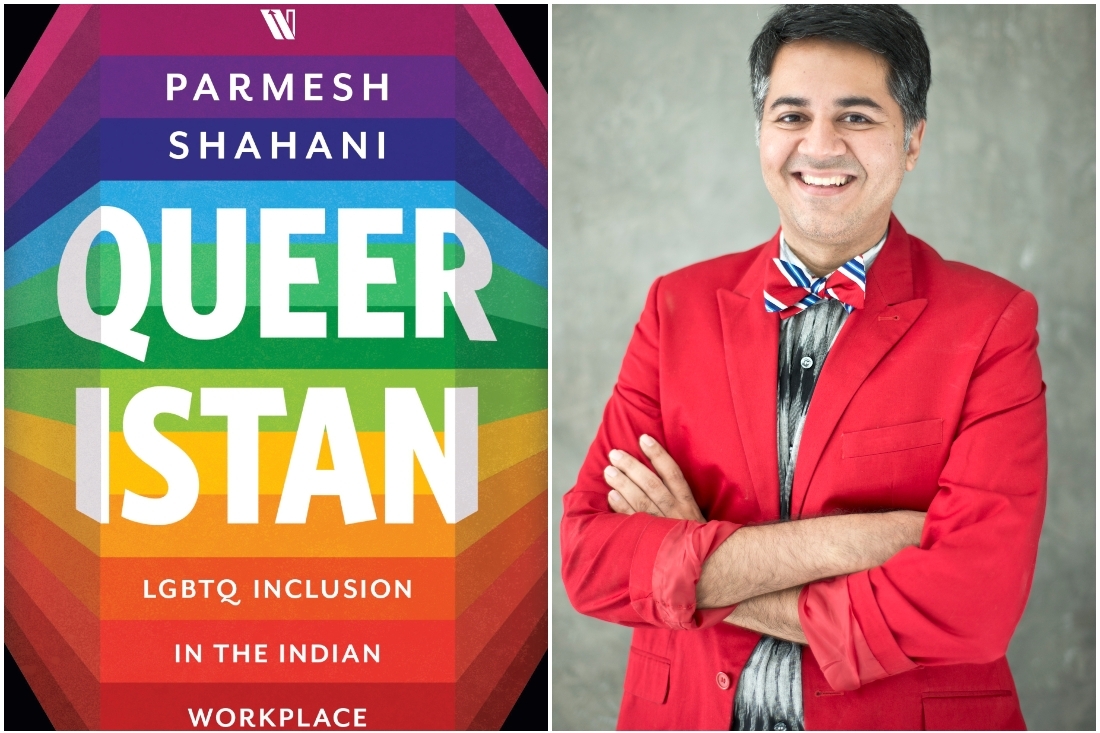

Image via Platform

Nilanjan Dey: Parmesh at some point in this book describes himself as a corporate activist. I’m going to read a paragraph from this book. “… in this ideal world, the human rights paradigm would be enough to bring about change. However, we aren’t there yet. So, hybrid people like me, corporate-activists who are pushing for change, have to use other strategies—profitability, innovation and so on—to make a business case for inclusion. How do we translate the language of human rights into these different and largely heterosexual corporate spaces? How do we help mostly straight business people see the range of queer experiences, and help the general public re-imagine what it means to be LGBTQ?” I want to understand a little bit about how you came to this, what were your motivations, what led you to kind of define this role for yourself and how do you see your work come out?

Parmesh Shahani: So, while I don’t like being in this position let me just say that, because it’s really very frustrating (having to make a business case). Just the fact that we exist, and mind you, we don’t even have to say that Queer people (exist as) 10% of any population, even if we were like 0.001%, we exist, we’re valid, we matter and we have the same rights as everyone else. So, from an Indian constitutional perspective, from a human rights paradigm, someone’s inherent worth should be a given. Everyone is equal and deserves to be treated in the same way, deserves to benefit in the same prosperity as everyone else and that means jobs, access to institutions, flawed institutions like marriage, but still, access to them, if you so choose to desire them, and happiness, a better life and so on. I’m very frustrated in all my corporate experiences that I have to in a sense put aside that very basic “don’t you care?” and actually use this language that I do, saying stuff like because you are a $5 trillion dollar global economy or a $200 billion dollar Indian economy, you should care. Include us because Mackenzie says that if you hire queer people your profitability will go up by 35%. This is all real data okay, I’m not making it up. It’s all cited in the book. Include us because Deloitte says that when you are more diverse and inclusive your innovation outcome goes up 8 times , include us because everyone, any survey right now of Millennials, Gen Z, people like you essentially, says that, they will not work for organisations which don’t care about the environment, which are not inclusive and so on and so forth. So, do I like making these elaborate pleas, include us because there are so many reasons, include us because of this, that…no! Do I do it? Yes! Because we do not live in a utopian world. Take gender for example. Despite work for so many decades on gender, women, and I use the term very broadly and generally, still die of foeticide, infanticide and other extensive ways we seem to have designed to kill our women. Also, women are still about 50% of our population but they are not 50% of educational institutions, workplaces and so on and as we go up the hierarchy, the asymmetry in representation is ridiculous. Take caste. Suraj Yengde, has written an incredible book “Caste Matters” that I invite all of you to read. It’s incredible, I mean there are 500 companies in India and guess how many of them have Dalit leaders or Dalit seniors? Zero. But, in my own company like Godrej, when I tried to bring up caste in boardrooms, it was like, “We don’t talk about all this, all that is over. Aren’t we living in a post-caste India? And I was like, just read the paper! There’s data that says that you know there is regional disparity in corporate spaces you know there are regions which are considered more mainstream whereas there are parts of India like the north-east etc. which are often not considered mainstream and then that has repercussions in terms of educational institutions, in terms of representation in media, and certainly jobs . There is religious disparity too Again, an amazing report by Parcham documents what it means being Muslim in Indian workplaces, Recently, the Led By Foundation ran a wonderful experiment on LinkedIn, where I think they applied to about a 1000 jobs posing as woman, but in one set of applications with a Hindu name and in another set of applications with a Muslim name. And the results in terms of who were shortlisted and who weren’t were astounding in their difference. Given that we don’t live in an equal and fair and just world, I resort to these arguments, knowing fully well that I am a part of neo-liberal capitalism, which is patently unfair and in which, people like me who are very marginal have to make our voices heard. We are marginal in terms of our visibility in these corporate spaces and our role is very precarious because at any point organisations may say we don’t want to be more inclusive for the sake of it . I therefore make my arguments knowing fully well my precarious and marginal position, appealing to the range of possibilities in the majorities that I see through because majorities have power, and from that position, I kind of squeeze in various possibilities for my people. So, it’s time-consuming, it’s laborious, it’s frustrating. Why do I do it? For various reasons. But let me share an interesting one. I was hanging with Sir Ian McKellen. Most of you are young and will know him as Gandalf or Magneto. People of my generation remember him as a legendary Shakespearean actor. The reason I know Ian McKellen is actually from school, he flirted with me one day and then I was like wait I can’t come back with you to London sorry but you be here in the Bollywood movies. Of course, he didn’t. Anyway, so, I was with him and he said something about the U.K. struggle: “Parmesh, it’s people like you and me to some extent who are their translation, who we need to be in all places to act as their translation. Because people in power will always be afraid of an activist on the street. And other than that, who else will engage.” So, any movement needs people to be, in a sense, sleeper cells who are staged everywhere. You need people to deal with the government, to push files and make it happen. You need people in educational institutions to say why can we not have an event like this? It’s not like the sky will fall and tomorrow everyone will find their company logos leap into giant rainbow hues and everything else. It will be fine with these people in corporate worlds and so on who can ask these questions, who can push for change from within. So, what Ian meant was, we need a very strong set of activists on the ground and in our courts and in healthcare and other kinds of work because if we have to create a better world it has to be in collusion with everyone who’s trying to do their bit out there. So I do my bit because I understand that change is going to be comprehensive, complicated and long term. I use the corporate world as an interesting vantage point to push change through. But I’m very clear, that I’m in the corporate world but I’m out - not of the jungle, not of the city. Kind of a border-crossing citizen, who’s everywhere and nowhere. And I think that now we need to create these positions of translations between these various things to bring about the change that we want from the ground up. Again, because of my background education and immense amount of privilege, I chose to sit here because I think I can make a bigger difference here. So, my question to all of you is, you’re going to graduate, some of you, maybe many of you will get fat salaries, a private house, car, spouse, and at some point, in life, at age 50 you’ll say who am I, what is the meaning of my life and all of that. Don’t wait for that midlife crisis. My plea to all of you is, you all are incredibly young, incredibly smart, incredibly privileged and a part of the education system. Guys once you begin to flourish, please try to use your location, your position at any stage in your life to bring about change, by doing whatever you can. I call that method jugaad resistance but like I really don’t want all of you who are sitting here to wait for some future when you will be able to bring about change. Every moment is a chance to actually shift the narrative.

Nilanjan Dey: I’m really glad you brought up jugaad resistance. I think you should talk a little bit about the method of this border-crossing citizen. But also, Jugaad resistance is a term you use in the book to describe your work . And I will obviously urge you to read the book where he goes into detail, but he gives a definition (at page 67 in Chapter 1 of Queeristan): “Jugaad resistance to me is a resourceful, solution-oriented opposition to establish ways of thinking in people. Jugaad resistance takes place when the revolutionaries locate themselves within the establishment, they wish for change, so that they can bring about innovative changes in the system from the inside.” And I wanted to ask you a little bit about how you came to this kind of method and what it looks like in practice, and a little reflection on your experiences with this.

Parmesh Shahani: In my life everything is retroactive. I do it and then I’m like oh let’s give this a go or whatever. I don’t think one day I’m going to do this. I’m going here or I’m going there, so whatever. I look like I do. I mean, it seems that way but when you write books you have phrases like this so one or two phrases last you for 5-6 years. So, let’s say for Homi Bhabha it’s hybridity. He’s been talking about hybridity for twenty years now . If you come from a media or cultural studies background you just need one or two such phrases. I came about it through practice, however. I realised that when I look at all the different things that I’ve done in life, they’re micro revolutions of change. And I think that when you add the micro-revolutions of change that’s when you get a big shift in society. I’m very fearful of macro-revolutions, and if you look at history, macro-revolutions don’t always play out the way you intend and they have unexpected consequences that need to be suffered by the ones who are the most vulnerable in each case. I’ve felt the same thing about those protesting against Assad and those who exited Syria, about eleven years ago, you know there was the resistance in Egypt, the Arab Spring, there was so much hope among young people in the Middle east and now years later their families have been killed and the countries are in a much difficult state, With micro revolutions however, the change, in a sense, doesn’t threaten the centre so much because if you do enough of these, you kind of change the nature of what the centre, the authority is because the narrative shifts slowly, yet ever so decisively. Greater engagement with LGBTQ+ issues is one such micro-revolution we managed to bring about in corporate India. Someone is doing it, TATA is doing it, if Tata is doing it then other factories will be like main bhi karta hoon. Before you know it, if you’re not talking about LGBTQ+ inclusion, you’re uncool. We didn’t say one day, that down with straight people and do this but moved bit by bit. I came upon this through practice, through my work in fashion, whether it was queer fashion magazines or through my work at Mahindra whether I was trying to reimagine what a Global Indian Corporation would look like, and certainly through my work at Godrej where I understood how much can you push without getting fired. For example, you know if everyone is trying to do just enough the texture changes overall. Say, you are in charge of your college festival, and need to plan souvenirs for the speakers. You can say, we will give a plant which is very nice, or you can say we will work with the Chamar project, with the artisans from the Chamar community, which is a historically disadvantaged caste-based community which has traditionally worked with leather but which because of the beef ban are threatened and now collectivised to create something called the Chamar Project, which works with recycled used tyres. So, it’s upcycling, it’s sustainability, its rubber, its eco-friendly, and its artisanal labour of a disadvantaged community. You can choose and say okay we’re going to spend this much on something, and we would rather spend it on this, because this will provide livelihoods to the disadvantaged. Your budget might be 500 rupees, but you can act. And then you’ve done Jugaad resistance because you’ve made a livelihood out of it. I’ve understood through my practice that if enough people do all this, , if say we have conferences where we have 20 speakers, let all 20 of them be women one year and see what happens. By the time people will notice, it’ll be too late and then someone will say, all women? Just say yeah, it’s been all men so many times, no one said anything then. And then suddenly you do it and it changes the texture of the conference, and then people say OMG. So, how I came about it is through practice, by saying that this really works, and I try and do it everywhere I can, whether it’s in conferencing, whether it's in this thing, or whether it’s in other kinds of engagements, I also do this for accessibility. Everyone says we must be accessible, but no one has sign-language interpreters in general, so in the last couple of years at culture lab, we didn’t wait until someone told us so, or we didn’t wait till someone said I’m coming on a wheelchair, is there a ramp? We just built a ramp for everyone. And because we built a ramp for everyone in the PWD community, people started WhatsApping that arre yeh building mein ramp hai so more people started coming. Because we started doing sign language interpretation for everyone on stage, suddenly people from the deaf community started joining us because they said, you know these people are doing sign interpretation. So, through little bits of resistance, you realise that it changes the texture of the game for everyone totally. So, I write about it because it worked.

Nilanjan Dey: No, I agree!

Parmesh Shahani: Does anyone want to share one good example of Jugaad resistance— that they have done while they were in this college, or that they are thinking of doing. Should we talk for a little bit? You have an example? Something that you want to do? Think of an idea.

Abhijit Rohi: So, there is this ADR society that we have, it organises a national competition Mediation Bombay, and this year for all the judges we actually gave them laptop bags made by Chamar foundation, so that is one thing that we did, plus as a part of getting students engaged with certain things, we also had a beach clean-up drive done as part of that entire event.

Parmesh Shahani: That’s great. Anyone else? Organisation people are doing all kinds of things, for instance. Hiring managers increasingly say don’t show me men’s resumes only, because the moment you show men’s resumes, psychologically it goes another way. Wherever you are, on whatever level you are, you can make a change, that’s the point.